Many people have been posting on Twitter about their accomplishments in 2017. My biggest one is that I have survived with the mental health almost intact because of an effort I started late last year. Coming to the end of yet another year on the tenure track, I feel like I made no significant progress: I still do not have an R01, I am still single, I am still trying to steady myself in my personal and prefessional life. Yet, I have fought as hard as it was humanly possible for me to keep going while safeguarding my physical and psychological sanity. I have given this year truly everything I had. Things have happened to continue to destabilize me, but I weathered and navigated the changes. Every grant I sent out was scored, every pre-proposal invited. I have worked hard to build a stonger community and support network around me. My mental stamina has paralleled my running one, where I trained and conditioned so that for the first time in a few years I didn't get an overuse injury at the end of the summer. The plan for 2018 is to train harder and run further than I ever have. Hopefully, the lab will follow.

In building the annual 'Year in Review' post where I go through the first post of every month, I realized that the theme of resilience was combined with philosophical musings about why we do this job. It's a good summary of what happened. The first couple of months in 2018 will decide what happens next...

January: Going big for the New Year: sticking to my resolutions. Sitting in the back of an Uber in London between Christmas and New Year's, I was listening to whatever was on the radio. The newscaster announced that a new study had shown that to lose weight after the holidays you have to set unrealistic expectations.

February: In the belly of the beast. NIH Early Career Review Part I: review. Last year I applied to the NIH Early Career Reviewer program, which was developed by the Center for Scientific Review (CSR) to train scientist with no previous NIH experience to review grants.

#3 2017 greatest hits

April: 4 years on the tenure track. The lab is turning 4 today! This year has been a heck of a ride.

May: Is the pre-tenure job search a thing? I recently posted a pool on Twitter about when to apply for a new faculty position when you already have one.

June: Is resilience the name of the game in academia? As I was going through one of the hardest days in my tenure-track experience, struggling to get grants and to keep projects staffed, a friend advised me: "Resilience is the name of the game in academia. Just keep going."

#1 2017 greatest hit

August: Hiring is hard, but firing is harder. Letting people go is one of the hardest decisions I had to make as an academic.

September: How much time should a new PI spend at the bench? Some time ago I saw Huda Zoghbi give a talk describing her career path and mentoring philosophy.

October: Are academic scientists cogs in the machine of education corporations? Are we as academic scientists running a small business renting space from a larger corporation (the university)? And if yes, is this attitude damaging how we train our students and postdocs?

December: How do you keep going on the tenure track? The blog just turned 5 in November. I missed the actual birthday because it was a crazy month, but I've been thinking about this milestone.

Pages

▼

Thursday, December 28, 2017

Friday, December 15, 2017

Is "go big or go home" the way to go in academic publishing?

For the past few years, I have been struggling to reconcile my tendency to build large complete stories for publication and the need to show productivity for grants and promotion. I have agonized about what would be a manuscript that would satisfy both requirements, while I had to contend with deadlines, reviewer requests, delays, and personnel leaving. I am still not sure of what is the right way...or if even a right way exists, so I thought I'd brainstorm this here and see what people think.

I was trained to build substantial mechanistic stories so that a phenomenon would be reported with a mechanism attached to explain it. But these take time. I was also trained, maybe naively, to follow the most interesting question and identify whatever approach was most suited to answer it, which has led me to use an array of approaches and not to be technically specialized. This takes even more time. When you are in a large lab with massive resources in an institution with all kinds of expertizes you can draw from, this is greatly intellectually stimulating and a lot of fun. When you are in a small place where you are the only person doing what you are doing, and sometimes the only person in your entire scientific discipline, suddenly this approach is not working so well.

I had to learn this the hard way applying for funding when reviewers couldn't quite place me and

questioned my qualifications to perform techniques I've been using for years. Despite having worked on a particular approach for a long time, I wasn't as prolific in publishing about it since I was building a larger story, and reviewers didn't believe I could do it. So I put a portion of the story together and published it, but they still said it wasn't enough. I looked at what I had, at my submission deadlines, and decided to break things apart a bit more. It broke my heart a little as I was cannibalizing another paper in progress to break it into smaller "single approach" pieces. Now, while I write yet another paper, which relies on some of the previously published data, I so wish I had kept everything together! It would have been so beautiful and cohesive, and now I have to do somersaults to make my point. There is another paper which has been in the works for 10 years now (yup, ten) because we have been learning new techniques which are taking years to perfect, and I wonder if it will be worth it.

I watch people who stuck it out and built one of these beautiful and cohesive mechanistic stories and I have to admit I am a little envious. Not necessarily because of the high-impact paper and the admiration of their peers, but because of the pride that comes with having a great piece of work to call your own. In giving a talk I can still place all the smaller pieces into a bigger picture. Yet, I cannot tell if it is as evident for others such as study section members, search committees, and university administrators, to see. In the end, my belief has always been that one has to strike the right balance between publishing a large story and not taking too long to do it and risk appearing unproductive. I still have not figured out how to walk this tightrope...

I was trained to build substantial mechanistic stories so that a phenomenon would be reported with a mechanism attached to explain it. But these take time. I was also trained, maybe naively, to follow the most interesting question and identify whatever approach was most suited to answer it, which has led me to use an array of approaches and not to be technically specialized. This takes even more time. When you are in a large lab with massive resources in an institution with all kinds of expertizes you can draw from, this is greatly intellectually stimulating and a lot of fun. When you are in a small place where you are the only person doing what you are doing, and sometimes the only person in your entire scientific discipline, suddenly this approach is not working so well.

|

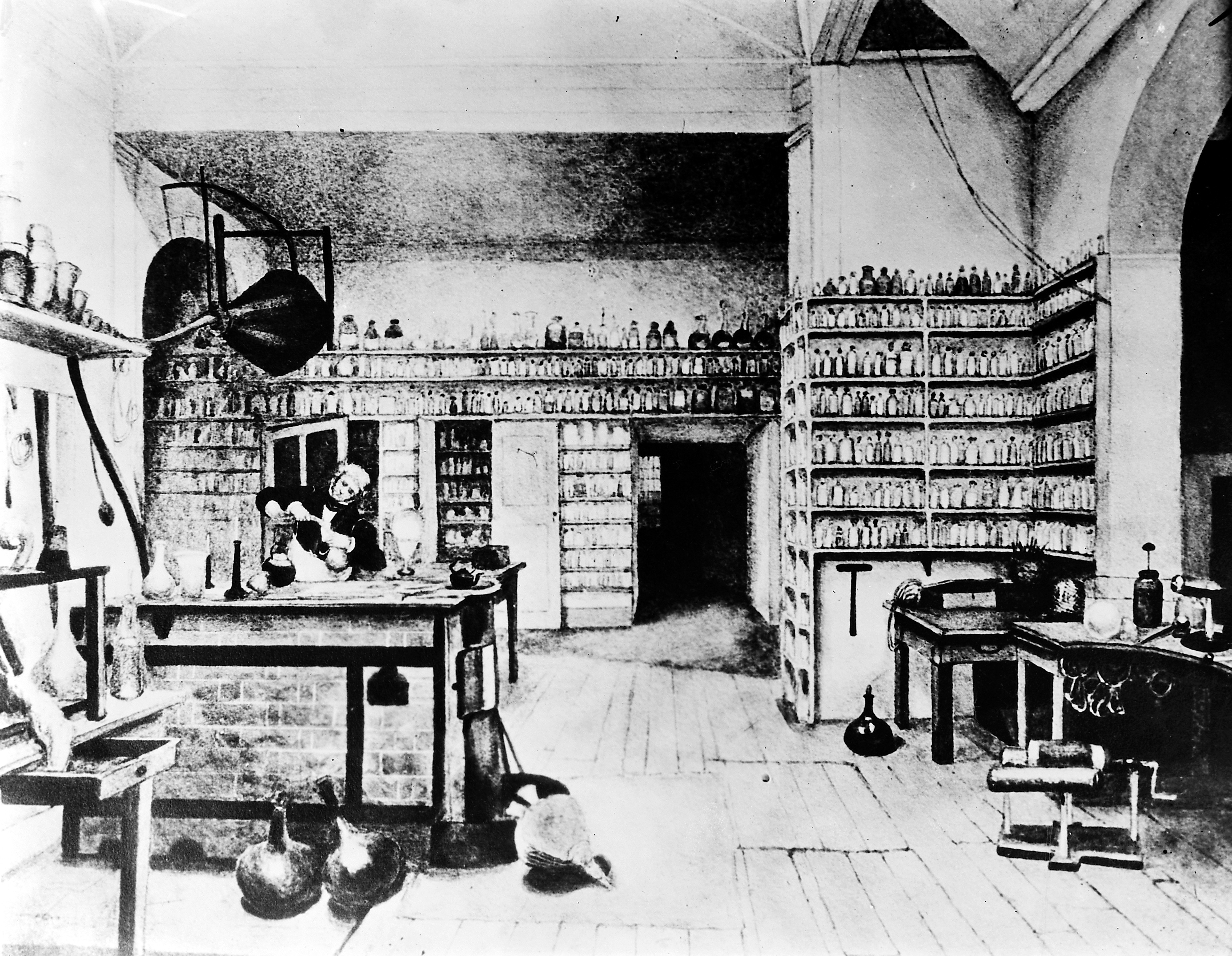

| Image: Adi Holzer, via Wikimedia Commons |

questioned my qualifications to perform techniques I've been using for years. Despite having worked on a particular approach for a long time, I wasn't as prolific in publishing about it since I was building a larger story, and reviewers didn't believe I could do it. So I put a portion of the story together and published it, but they still said it wasn't enough. I looked at what I had, at my submission deadlines, and decided to break things apart a bit more. It broke my heart a little as I was cannibalizing another paper in progress to break it into smaller "single approach" pieces. Now, while I write yet another paper, which relies on some of the previously published data, I so wish I had kept everything together! It would have been so beautiful and cohesive, and now I have to do somersaults to make my point. There is another paper which has been in the works for 10 years now (yup, ten) because we have been learning new techniques which are taking years to perfect, and I wonder if it will be worth it.

I watch people who stuck it out and built one of these beautiful and cohesive mechanistic stories and I have to admit I am a little envious. Not necessarily because of the high-impact paper and the admiration of their peers, but because of the pride that comes with having a great piece of work to call your own. In giving a talk I can still place all the smaller pieces into a bigger picture. Yet, I cannot tell if it is as evident for others such as study section members, search committees, and university administrators, to see. In the end, my belief has always been that one has to strike the right balance between publishing a large story and not taking too long to do it and risk appearing unproductive. I still have not figured out how to walk this tightrope...

Saturday, December 9, 2017

How do you keep going on the tenure-track?

The blog just turned 5 in November. I missed the actual birthday because it was a crazy month, but I've been thinking about this milestone. I realized that never in my wildest dreams I would have thought it would serve my readers and myself the way it has. It has followed me through twists and turns and going back through it gives me perspective on everything that happened. I went back to the beginning to read the post I wrote the day before I started my faculty position.

"Tomorrow I start the job I have been working towards for the past 15 years and I have been dreaming of since middle school. I always wanted to be a scientist and when I first joined a lab as an undergrad, I decided I wanted to run my own lab. I have had wonderful times and truly terrible times, when I have teetered on the edge of dropping out of college to man the cashier at a supermarket, dropping out of grad school to go write movies or just simply hide under a rock, leaving my postdoc to go work as a scientific consultant in finance or a policy advisor. For years, every day, I would wake up and think "Will I quit today?", and then I would choose my job as an aspiring academic scientist above anything else. Every day. And then, as I was interviewing for positions, something snapped into place..."

Little did I know that I would be back to the cycle in no time. This Fall as I went through the Nth federal grant proposal, dealing with the Nth admin disaster, and trying to keep my life together after months of antihistamines and steroids to calm my chronic hives, the thought of just quitting keeps coming up in my mind every day. Every day I wonder whether I want to go to work or not, whether I really want this job. I still consider working in policy, but have also developed a renewed interest in pharma.

What if I just resigned? A pragmatic friend asked if I have money ready for a transition to survive for 6-12 months, and I do. Heck, if I sold my place and moved to Bali or Costa Rica for a bit, I could probably rest easy on a beach for a couple of years...open a yoga studio...soak in some rays.

What if I just resigned? A pragmatic friend asked if I have money ready for a transition to survive for 6-12 months, and I do. Heck, if I sold my place and moved to Bali or Costa Rica for a bit, I could probably rest easy on a beach for a couple of years...open a yoga studio...soak in some rays.

I saved a Tim Ferriss piece on TED talking about visualizing what would happen if you did what you are afraid of, and your fears came true. So, I indulged the fantasy and did the exercise of going through what I would do if I actually decided to quit. There is no scenario where the people in my lab are not taken care of, and I don't end up on my feet...and most likely on a beach, at least temporarily.

So, as usual, it all boils down to focusing on what I really want. What is this job worth to me? Is it the job itself or the workplace? Is it worth chronically affecting my health over this? In talking to my friends in and out of academia, I find these are the questions so many in my cohort are struggling with. Including "Am I making myself miserable by expecting too much?" "Should I just settle for what I've got and deal with the feeling of failure?"

2016 was truly terrible for me and I did a huge amount of personal development work in 2017 to keep going with a certain degree of sanity and level-headedness. And I was reasonably productive. But despite being more empowered and having figured out what I want and what I need, I'm still getting unexplained hives, which tells me that something is very wrong. In January 2016, in what I feel was a watershed post for the blog openly discussing some very personal feelings which resonated with my readership, I set a two-year moratorium on quitting. I didn't know then that the two years that would follow would be has hard as hell. I continue to feel the erosion and the sand slipping beneath my feet. Can I survive this job if it continues to be this hard? What is this worth to me? But also, should I stop pushing as much as I do to meet my huge expectations? Again, what is this worth to me?

Honestly, I have found some answers, but I do not know all of them yet. My plan is to put in one more R01 in February 2018, see what happens with the grants that are in review now and then take stock of what is going on. The only thing I know is that something's gotta give for this to be sustainable...

"Tomorrow I start the job I have been working towards for the past 15 years and I have been dreaming of since middle school. I always wanted to be a scientist and when I first joined a lab as an undergrad, I decided I wanted to run my own lab. I have had wonderful times and truly terrible times, when I have teetered on the edge of dropping out of college to man the cashier at a supermarket, dropping out of grad school to go write movies or just simply hide under a rock, leaving my postdoc to go work as a scientific consultant in finance or a policy advisor. For years, every day, I would wake up and think "Will I quit today?", and then I would choose my job as an aspiring academic scientist above anything else. Every day. And then, as I was interviewing for positions, something snapped into place..."

Little did I know that I would be back to the cycle in no time. This Fall as I went through the Nth federal grant proposal, dealing with the Nth admin disaster, and trying to keep my life together after months of antihistamines and steroids to calm my chronic hives, the thought of just quitting keeps coming up in my mind every day. Every day I wonder whether I want to go to work or not, whether I really want this job. I still consider working in policy, but have also developed a renewed interest in pharma.

What if I just resigned? A pragmatic friend asked if I have money ready for a transition to survive for 6-12 months, and I do. Heck, if I sold my place and moved to Bali or Costa Rica for a bit, I could probably rest easy on a beach for a couple of years...open a yoga studio...soak in some rays.

What if I just resigned? A pragmatic friend asked if I have money ready for a transition to survive for 6-12 months, and I do. Heck, if I sold my place and moved to Bali or Costa Rica for a bit, I could probably rest easy on a beach for a couple of years...open a yoga studio...soak in some rays.I saved a Tim Ferriss piece on TED talking about visualizing what would happen if you did what you are afraid of, and your fears came true. So, I indulged the fantasy and did the exercise of going through what I would do if I actually decided to quit. There is no scenario where the people in my lab are not taken care of, and I don't end up on my feet...and most likely on a beach, at least temporarily.

So, as usual, it all boils down to focusing on what I really want. What is this job worth to me? Is it the job itself or the workplace? Is it worth chronically affecting my health over this? In talking to my friends in and out of academia, I find these are the questions so many in my cohort are struggling with. Including "Am I making myself miserable by expecting too much?" "Should I just settle for what I've got and deal with the feeling of failure?"

2016 was truly terrible for me and I did a huge amount of personal development work in 2017 to keep going with a certain degree of sanity and level-headedness. And I was reasonably productive. But despite being more empowered and having figured out what I want and what I need, I'm still getting unexplained hives, which tells me that something is very wrong. In January 2016, in what I feel was a watershed post for the blog openly discussing some very personal feelings which resonated with my readership, I set a two-year moratorium on quitting. I didn't know then that the two years that would follow would be has hard as hell. I continue to feel the erosion and the sand slipping beneath my feet. Can I survive this job if it continues to be this hard? What is this worth to me? But also, should I stop pushing as much as I do to meet my huge expectations? Again, what is this worth to me?

Honestly, I have found some answers, but I do not know all of them yet. My plan is to put in one more R01 in February 2018, see what happens with the grants that are in review now and then take stock of what is going on. The only thing I know is that something's gotta give for this to be sustainable...

Thursday, October 5, 2017

Are academic scientists cogs in the machine of education corporations?

My last post focused on how to motivate lab members during the last stretch of the tenure track and it spurred by far the most lively and interesting conversation we've had on this blog. The discussion touched many topics regarding motivation, results-only work environments, and how to run a lab in general. But there is one topic that often finds people deeply divided.

Are we as academic scientists running a small business renting space from a larger corporation (the university)? And if yes, is this attitude damaging how we train our students and postdocs?

Having grown up in a country where most universities are public, affordable and open to everyone, I have spent my entire career in the US grappling with this question and feeling uncomfortable when people extol the "tuition-driven" model, which for academic biomedical research becomes the "grant-driven" model. I'm not naive, I get how the cash flow will provide better services for students and more resources for researchers. But the cash flow also leads to the corporatization of education and research. The moment an institution starts to correlate space given to a lab with indirect recovery on grants on a bi-annual basis, research becomes a product...I will not digress on how this may push people to make bigger claims than necessary or to cut corners.

Having grown up in a country where most universities are public, affordable and open to everyone, I have spent my entire career in the US grappling with this question and feeling uncomfortable when people extol the "tuition-driven" model, which for academic biomedical research becomes the "grant-driven" model. I'm not naive, I get how the cash flow will provide better services for students and more resources for researchers. But the cash flow also leads to the corporatization of education and research. The moment an institution starts to correlate space given to a lab with indirect recovery on grants on a bi-annual basis, research becomes a product...I will not digress on how this may push people to make bigger claims than necessary or to cut corners.

I think many of us, new principal investigators, who have finally seem how the sausage gets made feel uncomfortable, as we are pulled between an ideal and the reality. The ideal is that I would like to be like Plato in the Symposium, discussing big ideas with like-minded individuals, training young minds towards major discoveries which will have a lasting impact on mankind. The reality is that I have to be mindful of accounting, HR and facilities, which I constantly write grant proposals to keep everything going. Trainees have to be productive because without money, I cannot keep myself or them employed and even if I find money to pay for their salaries, I still have to pay for all the supplies and reagents they need to do science. So, am I running a small business? All that I know is that in work-related conversations I can relate much more easily with friends in management or with a friend who owns a coffee shop, than with friends teaching in the humanities.

Newly minted Nobel laureate Jeff Hall's comments upon leaving science ring true "Might an institution imagine that it should devote part of its ‘capital fundraising’ toward endowing the ongoing research of its employees — at least so that no such effort would abruptly sink to the null point? The answer is ‘nice try: we will raise funds, but we'll put them all into building buildings — in order to fill them with additional hires, who will be as haplessly on-their-own as is ill-fated you.’ " It is telling that lately Nobel laureates feel the need to say (and I paraphrase) "I would never have made it today" (Peter Higgs, Physics) or "The whole publishing system is messed up" (Randy Schenkman, Physiology and Medicine). I expressed before how I sometimes feel this whole career trajectory is a Ponzi scheme, and that we should call it like it is. If you work for a private university, especially a school of medicine or hospital, you are most likely a cog in a massive money-making operation and it is very clear that if you do not bring in the money, there will be no room for you.

How does this reflect on how we train students and postdocs? I feel like we just need to be honest of the challenges and benefits. As a grad student I was very aware of labs that were on the verge of being shut down down the hall and professor transitioning to pharma and medicine because tenure doesn't mean much when you have to pay 70% of your salary. It helped me shape future strategies for survival and also prepare me for what to expect. I wish I had been exposed to different types of institutions in addition to the "massive fancy school of medicine", so I really try to make a point to show my trainees that there are multiple different ways of being an academic and of doing research...and that as in every job you can look for the right "fit". I also make them aware of the budgetary considerations of running a lab, of the need to look for independent funding for their salaries and their projects, and of the need to get papers done to show productivity. The part of me that would like to be in the Symposium, hates having to chop stories up to get papers out to support a particular grant application. I want my stories to be whole, elegant and solid, but the university and funding agencies want to look at numbers...and so we balance being a cog and dreaming of being a wheel running free on the road.

I think good training can still be achieved independently of the current funding situation and that it is a disservice not showing the students and postdocs what the pressures and considerations of running a lab are. Eventually, talking about it may even get someone to do something to change the system...

Are we as academic scientists running a small business renting space from a larger corporation (the university)? And if yes, is this attitude damaging how we train our students and postdocs?

Having grown up in a country where most universities are public, affordable and open to everyone, I have spent my entire career in the US grappling with this question and feeling uncomfortable when people extol the "tuition-driven" model, which for academic biomedical research becomes the "grant-driven" model. I'm not naive, I get how the cash flow will provide better services for students and more resources for researchers. But the cash flow also leads to the corporatization of education and research. The moment an institution starts to correlate space given to a lab with indirect recovery on grants on a bi-annual basis, research becomes a product...I will not digress on how this may push people to make bigger claims than necessary or to cut corners.

Having grown up in a country where most universities are public, affordable and open to everyone, I have spent my entire career in the US grappling with this question and feeling uncomfortable when people extol the "tuition-driven" model, which for academic biomedical research becomes the "grant-driven" model. I'm not naive, I get how the cash flow will provide better services for students and more resources for researchers. But the cash flow also leads to the corporatization of education and research. The moment an institution starts to correlate space given to a lab with indirect recovery on grants on a bi-annual basis, research becomes a product...I will not digress on how this may push people to make bigger claims than necessary or to cut corners.I think many of us, new principal investigators, who have finally seem how the sausage gets made feel uncomfortable, as we are pulled between an ideal and the reality. The ideal is that I would like to be like Plato in the Symposium, discussing big ideas with like-minded individuals, training young minds towards major discoveries which will have a lasting impact on mankind. The reality is that I have to be mindful of accounting, HR and facilities, which I constantly write grant proposals to keep everything going. Trainees have to be productive because without money, I cannot keep myself or them employed and even if I find money to pay for their salaries, I still have to pay for all the supplies and reagents they need to do science. So, am I running a small business? All that I know is that in work-related conversations I can relate much more easily with friends in management or with a friend who owns a coffee shop, than with friends teaching in the humanities.

Newly minted Nobel laureate Jeff Hall's comments upon leaving science ring true "Might an institution imagine that it should devote part of its ‘capital fundraising’ toward endowing the ongoing research of its employees — at least so that no such effort would abruptly sink to the null point? The answer is ‘nice try: we will raise funds, but we'll put them all into building buildings — in order to fill them with additional hires, who will be as haplessly on-their-own as is ill-fated you.’ " It is telling that lately Nobel laureates feel the need to say (and I paraphrase) "I would never have made it today" (Peter Higgs, Physics) or "The whole publishing system is messed up" (Randy Schenkman, Physiology and Medicine). I expressed before how I sometimes feel this whole career trajectory is a Ponzi scheme, and that we should call it like it is. If you work for a private university, especially a school of medicine or hospital, you are most likely a cog in a massive money-making operation and it is very clear that if you do not bring in the money, there will be no room for you.

How does this reflect on how we train students and postdocs? I feel like we just need to be honest of the challenges and benefits. As a grad student I was very aware of labs that were on the verge of being shut down down the hall and professor transitioning to pharma and medicine because tenure doesn't mean much when you have to pay 70% of your salary. It helped me shape future strategies for survival and also prepare me for what to expect. I wish I had been exposed to different types of institutions in addition to the "massive fancy school of medicine", so I really try to make a point to show my trainees that there are multiple different ways of being an academic and of doing research...and that as in every job you can look for the right "fit". I also make them aware of the budgetary considerations of running a lab, of the need to look for independent funding for their salaries and their projects, and of the need to get papers done to show productivity. The part of me that would like to be in the Symposium, hates having to chop stories up to get papers out to support a particular grant application. I want my stories to be whole, elegant and solid, but the university and funding agencies want to look at numbers...and so we balance being a cog and dreaming of being a wheel running free on the road.

I think good training can still be achieved independently of the current funding situation and that it is a disservice not showing the students and postdocs what the pressures and considerations of running a lab are. Eventually, talking about it may even get someone to do something to change the system...

Sunday, October 1, 2017

SfN 2017 Restaurant Guide and other tips

It's time to revamp my Society for Neuroscience (SfN) restaurant list. So much has happened since 2014 and you now get to go East of the Convention Center! New restaurants are opening all the time in the area. I'm already making reservations, organizing dinners, lunches, etc for the meeting, so now my readers get to reap the benefits of such activity and I get a break from my lab management rumblings.

Restaurants

The best source for restaurants in DC is usually the Washingtonian “Very Best Restaurant” list. I’ve never gone wrong trying one of these. Several are going to get booked quickly for the week of the conference from 5pm to 9pm, so make your reservations pronto. The list is across DC, Virginia and Maryland, so make sure you figure out where they are located.

This said these are my favorites in the Convention Center area (with their best restaurant # if they are on the list). Click the names for more info.

SOUTH:

Casa Luca (#35 - Italian) 1099 New York Ave NW (11th and NY Ave – 5 min walk) Great central Italian food from Fabio Trabocchi who is one of the most popular chefs in town. This is the cheapest of his restaurants which also include Fiola (#27) @ 601 Pennsylvania (6th and Indiana Ave – 12 min walk) and one of the hottest hot spots on the Waterfront FiolaMare (#5) @ 3100 K st NW in Georgetown (31st and K on the waterfront– Take the Circulator bus).

Zaytinya (#71 - Middle Eastern) 701 9th St NW (9th and G – 5 min walk) and Oyamel (Mexican) 401 7th St NW (7th and D – 12 min walk) are two iterations of the tapas empire of Jose Andres, who took over the DC food scene with Jaleo (#44 - Spanish) 480 7th St NW (7th and E – 10 min walk). Zaytinya and Oyamel are awesome. Small tapas to share of Turkish/Greek or Mexican inspiration. The tequila selection at Oyamel is extensive. Jaleo I find kind of blah so for tapas I go elsewhere…see North West.

Rasika (#11 - Indian) 633 D St NW (6th and D) is very famous and Michelle Obama's favorite, but I've never been able to get in there.

Brasserie Beck (Belgian bistro) 1101 K St NW (11th and K - 5 min walk) Belgian spot for mussels, steak frites and hundreds of beers on the menu.

In the relatively newly opened City Center complex my faves are:

Centrolina (#51 - Italian) 974 Palmer Alley NW is a small hip Italian restaurant and market with a seasonal ever-changing menu. I love it!

Daniel Boulud's DBGB (#80 - French) 9th and I, with a fantastic selection of charcuterie.

If you want burgers the closest Shake Shack is on 9th and F, Bolt Burgers by the convention center (11th and L/Mass) is okay.

NORTH WEST:

Estadio (#24 - Spanish tapas) 1520 14th St NW (14th and Church, after P – 18 min walk) has my favorite tapas in the area. Make sure to try the slushito…a slushi for adults.

Le Diplomate (#18 - French Bistro) 1601 14th St NW (14th and Q). Hard to get into French spot from the people who brought you Buddakan and Morimoto in NYC. Good brunch.

Ted’s Bulletin (American) 1818 14th St NW (14th and S). A DC staple with its original in Capitol Hill, it’s worth a visit even if just for their homemade pop tarts and adult milkshakes. Also good lunch.

Kapnos (#30 - Greek tapas) 2201 14th St NW (14th and W - yes, you can go that far North now. The U street area is happening) Chef Mike Isabella twist on Greek tapas.

Kapnos (#30 - Greek tapas) 2201 14th St NW (14th and W - yes, you can go that far North now. The U street area is happening) Chef Mike Isabella twist on Greek tapas.

El Rinconcito Café (Salvadorean/Mexican) 1129 11th St NW (11th and M) a hole in the wall with awesome tamales, papusas and burritos. Good for cheap but massive lunch or dinner.

And last but not least, EAST:

Farmers&Distillers (American) 600 Mass Ave NW (6th and Mass) huge new spot for everything locally sourced, artisanally made, grass fed. Also has own distillery.

Ottoman Taverna (Turkish) 425 I st NW (4th and I) another massive new restaurant with great Turkish fare

Ottoman Taverna (Turkish) 425 I st NW (4th and I) another massive new restaurant with great Turkish fare

Busboys and Poets (Breakfast/brunch) 1025 5th St NW (5th and K) a DC staple with multiple locations

A Baked Joint (Breakfast/brunch) 440 K St NW (4th and K) new Brooklyn-style breakfast place and OMG the "morning sammies" are awesome (if you can stand in line for 45mins on a Sat morning)

Places with lots of restaurants to explore are also Georgetown and Capitol Hill. Georgetown is easily reached on the Circulator bus (1$ fare).

Also in DC you have to try food truck food for lunch. Closest trucks to the Convention Center will be in McPherson Square between 13-14th and I-K. A lot of good restaurants have trucks and all will take credit cards. Trucks can be tracked with Food Truck Fiesta and are usually only around Mon-Fri.

Other useful places

Closest supermarkets: Safeway (New York and 5th just walk on NY from the Convention Center) is open 24 hours and Whole Foods is on P between 14th and 15th

Closest CVS: tucked away on 10th and L

For a moment of peace the National Portrait Gallery/American Art Museum building is just a few blocks away at 8th and F and you can sit and use the free Wi-Fi in the Foster re-designed courtyard or walk around the exhibits. Both the American Art and the NPG have lovely things....unless of course you want to go for a real art trip to the National Gallery (Should I mention the only Da Vinci in the American continent?).

For the runners:

3mi #1: from the Convention Center area go straight south to the Mall, run west along the Mall, run back up on 17th and loop east on J until you hit New York Ave all the way back. This is also a good evening route...Secret Service is every 300ft or so.

3mi #2: go straight south to the Mall, run EAST along the Mall up to 1st street and the Capitol, wave your fist at Congress demanding more science funding and sanity, loop back along the south side of the mall and come back up on 9th or 10th.

4mi: Combine #1 and #2

5mi #1: Combine #1 and #2, but also go say hi to Lincoln at the west end of the Mall.

5mi #2: go straight south to the Mall, at the Washington Monument keep left and go towards the Tidal Basin, run all the way around, say "Hi" to TJ in his marble temple, slow down at the FDR Memorial which is really awesome, dodge the ducks, avoid the mobs at the MLK Memorial...here you can run back, or since you've come this far, make 5.5/6mi, go say "Hi" to Lincoln via WWI and WWII...if it's early enough in the morning you can try and pull a Rocky on the steps.

Water fountains for your convenience at every Memorial :)

Sunday, September 24, 2017

How do you get people complete projects during the tenure push?

My last post about getting back to the bench and figuring out how much time a new investigator should take from teaching and admin work spurred a lot of discussion about the pros and cons of having the PI active in the lab. It made me think about motivating and inspiring people. I have been interested in motivation for a long time. When I was a PhD student a new PI came into our lab at 8:30pm and just point blank asked me and the postdoc laboring at our computers "Why are you still here? My people are all gone. How do I get them to stay?" We kind of looked at each other and shrugged "I don't know..." Our boss had been gone for hours to go home to her family, and whether she was there at all didn't make any difference on our hours. We just needed to get work done. That started me thinking about why people commit to a project. Mind, the point here is not the number of hours you spend on it which can vary depending on family and other obligations, but the desire to get results and complete your work. How do you get lab members that are engaged, detail oriented and passionate about their science? You hire this type of person, you'll say. Sure, but you also have to keep them motivated...

When I started the blog 5 years ago (😱) some of my very first posts were about motivation, and I still need to remind myself of that advice from time to time. In one of my first posts I posted about a great book, Drive, by Daniel Pink who discusses behavioral research suggesting that once certain basic salary requirements are met people are motivated by Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose. They need to work independently and develop their own ideas. They need to feel that they have mastered complex theories and techniques. They need to have a good reason for why they are doing what they are doing.

This all sounds great! This is exactly what motivates me. But everyone moving at their own speed or following their own ideas could work for a large well-funded lab but may not be the best way to get a small research lab to finish the papers and projects we need to survive the tenure-track. I have already assigned lab peeps to specific priorities, but some of my mentors want me to pull people off their own projects to help on finishing other people's things. I'm debating whether that would help or hurt our progress. Will I be disrupting lab dynamics and upsetting egos? And what about their own projects? This doesn't really promote autonomy or mastery...

.jpg) It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?

It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?

I think I need to better express my sense of urgency, keep stricter deadlines, and shift priorities if necessary...and of course get back in the lab! Maybe the camaraderie of working through this together is that is really needed. In the meantime, this handy productivity guide from the Harvard Business Review may also help!

Photo credit: By PeterJBellis from England (White Water Rafting (on The Nile) - Wikimedia Commons

When I started the blog 5 years ago (😱) some of my very first posts were about motivation, and I still need to remind myself of that advice from time to time. In one of my first posts I posted about a great book, Drive, by Daniel Pink who discusses behavioral research suggesting that once certain basic salary requirements are met people are motivated by Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose. They need to work independently and develop their own ideas. They need to feel that they have mastered complex theories and techniques. They need to have a good reason for why they are doing what they are doing.

This all sounds great! This is exactly what motivates me. But everyone moving at their own speed or following their own ideas could work for a large well-funded lab but may not be the best way to get a small research lab to finish the papers and projects we need to survive the tenure-track. I have already assigned lab peeps to specific priorities, but some of my mentors want me to pull people off their own projects to help on finishing other people's things. I'm debating whether that would help or hurt our progress. Will I be disrupting lab dynamics and upsetting egos? And what about their own projects? This doesn't really promote autonomy or mastery...

.jpg) It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?

It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?I think I need to better express my sense of urgency, keep stricter deadlines, and shift priorities if necessary...and of course get back in the lab! Maybe the camaraderie of working through this together is that is really needed. In the meantime, this handy productivity guide from the Harvard Business Review may also help!

Photo credit: By PeterJBellis from England (White Water Rafting (on The Nile) - Wikimedia Commons

Monday, September 4, 2017

How much time should a new PI spend at the bench?

Some time ago I saw Huda Zoghbi give a talk describing her career path and mentoring philosophy.

Huda is a giant in neurogenetics and neuroscience in general and she is one of the people who shaped the study of neurodevelopmental disorders. She is also well known to be a great mentor, in particular to women. One piece of advice that Huda gave to young investigators was to be at the bench all day every day, work closely with your lab and fill the lab with grad students. As a young PI you are the best postdoc you can get and you are the one who can continue to make the big discoveries. Grad students will take a while to train, but the time taken will pay off.

In theory, I would love to do that. But my question is "How?" How could I have responsibly hired 3-4 students in a very small program where I had 3 rotation students in 3 years? The start-up also does not cover the time necessary to graduate multiple students. With the fluctuations in funding, I could initially guarantee 2-3 years in salary for people and now I'm down to 1 year, so I have stopped taking rotation students altogether. I have spoken to multiple friends in the same situation and some of them also have to teach one or two classes per semester giving them even less time for mentoring students.

In theory, I would love to do that. But my question is "How?" How could I have responsibly hired 3-4 students in a very small program where I had 3 rotation students in 3 years? The start-up also does not cover the time necessary to graduate multiple students. With the fluctuations in funding, I could initially guarantee 2-3 years in salary for people and now I'm down to 1 year, so I have stopped taking rotation students altogether. I have spoken to multiple friends in the same situation and some of them also have to teach one or two classes per semester giving them even less time for mentoring students.

For this reason, I have ended up running a postdoc and technician-heavy group, but as the tenure crunch is getting closer, I'm wondering if I should jump in to make things move faster. In talking to friends who just went through the process I realized I'm not an exception. I'm still the most advanced and technically skilled postdoc I can get. So my dilemma at this time is whether I need to get better organized with writing grants and papers, and carve out time for experiments. I was independent as a student and postdoc working on my own projects and ideas, so I tend to follow the same model of letting everyone work on their project and paper. Yet, I'm worried this is hurting more than helping and that I should get "all hands on deck" on a couple of papers and reroute resources to get things done.

What is your experience? How much time should a new PI spend at the bench? Does it make sense for me to step in to help with experiments or to start the riskiest projects and only give them off to trainees once the preliminary data is solid? Comments and advice would be greatly appreciated.

Huda is a giant in neurogenetics and neuroscience in general and she is one of the people who shaped the study of neurodevelopmental disorders. She is also well known to be a great mentor, in particular to women. One piece of advice that Huda gave to young investigators was to be at the bench all day every day, work closely with your lab and fill the lab with grad students. As a young PI you are the best postdoc you can get and you are the one who can continue to make the big discoveries. Grad students will take a while to train, but the time taken will pay off.

In theory, I would love to do that. But my question is "How?" How could I have responsibly hired 3-4 students in a very small program where I had 3 rotation students in 3 years? The start-up also does not cover the time necessary to graduate multiple students. With the fluctuations in funding, I could initially guarantee 2-3 years in salary for people and now I'm down to 1 year, so I have stopped taking rotation students altogether. I have spoken to multiple friends in the same situation and some of them also have to teach one or two classes per semester giving them even less time for mentoring students.

In theory, I would love to do that. But my question is "How?" How could I have responsibly hired 3-4 students in a very small program where I had 3 rotation students in 3 years? The start-up also does not cover the time necessary to graduate multiple students. With the fluctuations in funding, I could initially guarantee 2-3 years in salary for people and now I'm down to 1 year, so I have stopped taking rotation students altogether. I have spoken to multiple friends in the same situation and some of them also have to teach one or two classes per semester giving them even less time for mentoring students.For this reason, I have ended up running a postdoc and technician-heavy group, but as the tenure crunch is getting closer, I'm wondering if I should jump in to make things move faster. In talking to friends who just went through the process I realized I'm not an exception. I'm still the most advanced and technically skilled postdoc I can get. So my dilemma at this time is whether I need to get better organized with writing grants and papers, and carve out time for experiments. I was independent as a student and postdoc working on my own projects and ideas, so I tend to follow the same model of letting everyone work on their project and paper. Yet, I'm worried this is hurting more than helping and that I should get "all hands on deck" on a couple of papers and reroute resources to get things done.

What is your experience? How much time should a new PI spend at the bench? Does it make sense for me to step in to help with experiments or to start the riskiest projects and only give them off to trainees once the preliminary data is solid? Comments and advice would be greatly appreciated.

Friday, August 18, 2017

DonorsChoose challenge to support social sciences and tolerance in the classroom

So many friends and colleagues have been posting on social media about how they feel that the world is spinning out of control, and that the basic principles of human decency, mutual respect, and acceptance are being trampled.

Inspired by blogger DrugMonkey's challenges to fund as many school projects as possible via DonorsChoose, I decided to set up a new challenge. DonorsChoose is a fantastic charity portal where teachers can post funding requests for specific school projects and donors choose which ones to fund. I selected a group of projects focused on current events, social studies and history, and teaching about diversity and immigration. The goal is that with the new school year starting we want kids to learn what is going on around their communities and around the world. We want to inspire a new generation of citizens and leaders.

So here it goes: click on the projects and donate whatever you can. Even the equivalent of a daily latte at $5 can make a difference and some projects have other donors matching donations 100%. You will help kids and teachers develop strategies for a better world.

Mrs. Gaines (NC): Love, Tolerance, Acceptance and Diversity ($257 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Mr. M (CA): Help my refugee students ($828 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Mrs.VanderKamp (MI): Cooperation in the classroom and around the globe ($582 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Ms. Cunningham (TX): Tolerance and compassion begin early ($240 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Mrs. Froning (NC): It's all about the TIMES ($175 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Ms. Hepburn (FL): "Time" to be tolerant ($833 total - 100% match) FUNDED

Mr. Gaspard (IN): Everything you need to ace American history in 1 notebook ($155 total) FUNDED

I will strike out projects as they get funded and add new ones. Maybe we will get DrugMonkey out of retirement...

Inspired by blogger DrugMonkey's challenges to fund as many school projects as possible via DonorsChoose, I decided to set up a new challenge. DonorsChoose is a fantastic charity portal where teachers can post funding requests for specific school projects and donors choose which ones to fund. I selected a group of projects focused on current events, social studies and history, and teaching about diversity and immigration. The goal is that with the new school year starting we want kids to learn what is going on around their communities and around the world. We want to inspire a new generation of citizens and leaders.

So here it goes: click on the projects and donate whatever you can. Even the equivalent of a daily latte at $5 can make a difference and some projects have other donors matching donations 100%. You will help kids and teachers develop strategies for a better world.

I will strike out projects as they get funded and add new ones. Maybe we will get DrugMonkey out of retirement...

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Fighting loneliness on the tenure track

My emergency contact is moving away. One of the friends who convinced me to move where I am was fired earlier this year for not having an R01 grant. She found a new (much better) job, was awarded a large foundation grant and will likely get her R01 in the next month or so. She's heading to be awesome somewhere else. The other good friend I had made after moving to "New PI town" moved away a few months ago also for a job opportunity closer to her family and boyfriend. So, who should be my emergency contact now? Likely someone in my family in Europe, since I don't have close friends nearby.

What I'm really asking is: how much loneliness is one supposed to put up with for the sake of their job? Many jobs may push you to move around for career advancement, but I do not know any other one where getting a new job takes 1-3 years and will most likely mean you have to move somewhere else. Being on the tenure track adds a level of restraint where you may not be able to be completely honest with senior or junior colleagues. In addition, being the boss is a lonely job, as you can be friendly and caring, but not the one to share your deepest fears and doubts. Not being in a relationship makes things more lonely, but relationships can complicate things. Some people move to less than ideal situations to follow their significant other. Other couples are stuck living in different cities because two academic positions in the same place are hard to find. Last but not least, studies have shown that it becomes harder and harder to form close friendships after a certain age,

This sounds dire. What is an academic to do? When deep ties built during graduate school and postdoc years are severed and friends are scattered all over, conferences and seminars become as much about science as about getting together and catching up. I never really appreciated how critical this is for my well-being until I started as an Assistant Professor. Other networks are also available to get support and develop a sense of belonging. Twitter provides a broad and supportive scientific community, though trolls and the constant barrage of news and opinions sometimes require taking a step back every now and then. Nonetheless, friendships can be forged on the site. The New PI Slack (no relations to me) is a supportive community for early stage investigators which is now hosting more than 1000 academics in constant discussions about running a lab, writing grants, training, teaching and many other topics. What matters is that there are A LOT of other people out there going through the same things and having the same problems I have. Science in academia doesn't have to be so lonely.

I will miss my friends terribly, but everyone has gotta do what they gotta do. Old friends are still an email, a phone-call or a flight away. And I am glad there are all these other groups available. I am still not convinced that you cannot develop new strong friendship after 30 or 40, in real life and online.

What I'm really asking is: how much loneliness is one supposed to put up with for the sake of their job? Many jobs may push you to move around for career advancement, but I do not know any other one where getting a new job takes 1-3 years and will most likely mean you have to move somewhere else. Being on the tenure track adds a level of restraint where you may not be able to be completely honest with senior or junior colleagues. In addition, being the boss is a lonely job, as you can be friendly and caring, but not the one to share your deepest fears and doubts. Not being in a relationship makes things more lonely, but relationships can complicate things. Some people move to less than ideal situations to follow their significant other. Other couples are stuck living in different cities because two academic positions in the same place are hard to find. Last but not least, studies have shown that it becomes harder and harder to form close friendships after a certain age,

|

| Children's voyage (Wikimedia Commons) |

I will miss my friends terribly, but everyone has gotta do what they gotta do. Old friends are still an email, a phone-call or a flight away. And I am glad there are all these other groups available. I am still not convinced that you cannot develop new strong friendship after 30 or 40, in real life and online.

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

Hiring is hard, but firing is harder...

Letting people go is one of the hardest decisions I had to make as an academic. Not only because it came with the feeling that I had failed as a mentor, but also because of the overall HR stress associated with it.

As a student and postdoc I often observed situations where principle investigators (PIs) would not fire an unproductive and disruptive element for years, leading to infighting in a tense and unwelcoming workplace and tens of thousands of grant money lost. In many cases, these were large laboratories where the PI was aware and upset about the situation, but mostly ignored it and let it play its course. When this happens in a small lab things can get much worse. There is nowhere to hide and the $40-60K in salary lost in keeping someone who does not do their jobs can mean reduced resources for the lab, less support for other people, and delays in getting grants and papers threatening the long term survival of the entire group.

I'm not talking about when someone is struggling and needs coaching or a different communication approach, but when after multiple discussions and interventions someone is unable or refuses to follow instructions or reach objectives. When everyone else in the lab has decided that they do not want to interact with the person, or when the person has shown no respect for other people's work or animal welfare. In general, managers take longer than they should to fire employees because it is uncomfortable and this can take even longer in science. As an educator, I consider everyone in the lab, including the technicians, as a trainee. They have to do a job, but it is my job to train them and help them succeed. So, everyone I had to let go felt like a personal failure. I mostly think that the lab is a better environment because of it, but part of me always feels that I could have done more as a boss and as a mentor to find the one thing that could have motivated and inspired them. I'll never know. The additional damage they could have done to our progress and finances could have been catastrophic and I couldn't take the risk to let the situation progress any longer.

In some cases the decision will be mutual and the situation so uncomfortable for both parties that the employee decides to leave, but sometimes you will have to have the dreaded discussion. It is critical to have the entire process mapped out by HR and know exactly what you can and cannot say. HR does not take these situations lightly and has a lot of rules. Many of these rules are in place to protect the institution and you. There are some good primers out there, but the bottom line is that the interaction is all about the employee and easing them through the transition. "Your feelings are irrelevant" and you need to prepare (a helpful list of questions from Monster). An HR representative will likely want to be there with you and they can coach you through the interaction and the exact words to use. Since research staff positions are attached to grants, poorly performing individuals can be let go when grants end and lab salaries need to be reshuffled. In this instance, performance should not be included in the termination narrative at any time and the only explanation given should be about funding. Otherwise, an employee can request a performance improvement plan (PIP) or sue the university for wrongful termination.

It's not easy and it shouldn't be, but ample warning, a clearly defined course of action, and a steady demeanor can make this incredibly stressful event go smoothly.

In some cases the decision will be mutual and the situation so uncomfortable for both parties that the employee decides to leave, but sometimes you will have to have the dreaded discussion. It is critical to have the entire process mapped out by HR and know exactly what you can and cannot say. HR does not take these situations lightly and has a lot of rules. Many of these rules are in place to protect the institution and you. There are some good primers out there, but the bottom line is that the interaction is all about the employee and easing them through the transition. "Your feelings are irrelevant" and you need to prepare (a helpful list of questions from Monster). An HR representative will likely want to be there with you and they can coach you through the interaction and the exact words to use. Since research staff positions are attached to grants, poorly performing individuals can be let go when grants end and lab salaries need to be reshuffled. In this instance, performance should not be included in the termination narrative at any time and the only explanation given should be about funding. Otherwise, an employee can request a performance improvement plan (PIP) or sue the university for wrongful termination.

It's not easy and it shouldn't be, but ample warning, a clearly defined course of action, and a steady demeanor can make this incredibly stressful event go smoothly.

Thursday, June 15, 2017

Is resilience the name of the game in academia?

As I was going through one of the hardest days in my tenure-track experience, struggling getting grants and keeping projects staffed, a friend advised me: "Resilience is the name of the game in academia. Just keep going." And so I did, I doubled down on my efforts and ticked every possible box on the tenure check-list...apart from one...an NIH R01 grant. I applied at every funding cycle revamping old applications and drafting new ones, went from Not Discussed last year to two not-fundable, but decent scores in 2017. And so we keep going through the slog of applying to an NIH grant every four months until something hits. "Wishin' and hopin' and thinkin' and prayin'..."

Lately I've been faced with what happens if something does not hit. A very close friend was let go and will close her lab in the next couple of weeks. Then, this week Dr. Becca (@doc_becca) who has been a beacon for junior faculty everywhere got one more not-fundable score on an R01 application, and may not get tenure. In both cases, these women are recognized young leaders in their respective fields, speakers at national conferences and part of national society committees, in addition to being great mentors and good citizens at their universities. In Dr. Becca's words...

I didn't mean to start this as an hopeless post. I'm still wishin' and hopin'. Still hustlin' to come up

with some new ways to tell my stories so that journal referees, conference attendees, AND NIH reviewers are wowed. I'm just wondering if resilience is necessary but not sufficient, and if luck is the defining factor. The good fortune to have the right mentors at the right time to guide your applications, the right reviewers, the right star alignment for a favorable outcome. Then everything is a gamble, and all a young scientist can do is her/his best. If you are one of the lucky ones, how do you move forward from there? How do you motivate your trainees through such instability? But also how does this impact the status of scientific development and innovation at a national and global level? These are the days I would really want to move into policy-making to fix this, but then the most exciting science of my career is sitting there waiting to get done...and I need to find money to do it. So, I get back to my work and try not to think about any of this, while somewhere in the back of my mind still lurks the suspect that I'm being conned...

Lately I've been faced with what happens if something does not hit. A very close friend was let go and will close her lab in the next couple of weeks. Then, this week Dr. Becca (@doc_becca) who has been a beacon for junior faculty everywhere got one more not-fundable score on an R01 application, and may not get tenure. In both cases, these women are recognized young leaders in their respective fields, speakers at national conferences and part of national society committees, in addition to being great mentors and good citizens at their universities. In Dr. Becca's words...

What if you do everything you are supposed to do and the NIH still doesn't believe you? What if you are doing cool and innovative science which doesn't fit a certain mold and the reviewers don't get it? You can say: "Well, maybe you did not explain it well enough." "Maybe, though it was explained well enough to get nice papers and talk invites." It just feels like there is something fundamentally broken with the system and that wishin' and hopin' is not going to cut it. I have completely changed strategy with every grant I have sent in. When I have responded to reviewers comments by doing everything requested, things have gotten worse instead of better. Taking a look on the inside of NIH peer review earlier this year gave me some prospective. I don't necessarily think that peer review itself is broken. I enjoyed participating and found that everyone was fair, but I realized that the 10-15% pay lines introduce an element of pure luck which has nothing to do with your worth as a scientist. And this is particularly punishing to women as they receive lower scores than men. I have some hope in the new NIH initiative to increase new investigator pay lines to 25% across the board, but this still doesn't fix the overall lack of support that many junior and mid-career faculty receive from their institutions.I have done EVERYTHING I was supposed to. I published in good journals. I gave talks. I designed classes. I mentored students.— Dr Becca, PhD 🐘 (@doc_becca) June 12, 2017

I didn't mean to start this as an hopeless post. I'm still wishin' and hopin'. Still hustlin' to come up

with some new ways to tell my stories so that journal referees, conference attendees, AND NIH reviewers are wowed. I'm just wondering if resilience is necessary but not sufficient, and if luck is the defining factor. The good fortune to have the right mentors at the right time to guide your applications, the right reviewers, the right star alignment for a favorable outcome. Then everything is a gamble, and all a young scientist can do is her/his best. If you are one of the lucky ones, how do you move forward from there? How do you motivate your trainees through such instability? But also how does this impact the status of scientific development and innovation at a national and global level? These are the days I would really want to move into policy-making to fix this, but then the most exciting science of my career is sitting there waiting to get done...and I need to find money to do it. So, I get back to my work and try not to think about any of this, while somewhere in the back of my mind still lurks the suspect that I'm being conned...

Monday, May 29, 2017

A scientific Sophie's Choice

One of my mentors once said that women have a harder time letting projects go. Both as it relates to the level of perfection that needs to be achieved to publish and to the general attachment to an idea that keeps resurfacing over the years. Right now, I am struggling with the decision of whether to let a project go.

If you have not seen or read Sophie's Choice, it's worth it. Meryl Streep is amazing in it and she won an Oscar. Sophie is a Polish woman captured by the Nazis with her two children. As she enters Auschwitz she has to decide which one of her children will die. Which one will be more likely to survive the camp? Which one is the weakest needing more protection? Which one is the favorite? I have written many times of how my lab is split between two major projects, of how they are different in many ways, which is messing with my identity as a scientist. In addition, while they both were funded, one project has been struggling from the start and has required a huge amount of my attention and effort. The right people to carry it on have not materialized, so I have kept it going mostly by myself by sheer willpower and elbow grease. As I make the final tenure push, I have to decide whether to let it go. This feels like cutting out a piece of myself. This is the project that got me my job. It's the one that was my pride and joy as a postdoc, the one that made a beautiful job talk, and the one that was supposed to support my independent lab for years to come. It was not supposed to falter. It taught me that no matter how many brilliant ideas you have, your environment and your hires are critical for success. It required infrastructure that did not exist where I am and that had to be built from scratch without the proper support. It required equipment that was not available. Some major senior faculty stakeholders left to pursue other opportunities, collaborators who signed up to help did not deliver on their parts of the work. Funding runs out in a few months. The reviewers of the R01 application based on this work thought the hypothesis was interesting, but they wanted me to prove it. Which I cannot do without more money. So there. All in all, over four years we are talking of an investment of around $800K and I have to decide how much more time and money I really want to devote to it. The seed fell on ground that was not fertile enough for it to grow quickly.

The other child had been the recalcitrant one. Uncooperative and slow to develop, but it brought in money, so I kept it. I added it almost as an afterthought in my job talk, because I had a freaking K99 on it, so it would have looked weird if I ignored it. Opposite to the first one, this project required all my attention during my postdoc without much reward. Now the duckling has morphed into the most beautiful swan and we have three major papers in the pipeline. Because of the multiple personnel losses last summer, it stalled for six months and is now picking up again with new talented postdocs. My mentors tell me to cut my losses and go all in with this second project. Focus on getting the papers out to make this become my sure bet for an R01. Yet, I have come to my faculty position with an identity and a hypothesis I have been pursuing for 10 years, and I am faced with forsaking it. My gut is confused. I do not have the luxury of time to figure things out. In less than one year I have to start assembling my tenure package and I need an R01 to survive. I love both my projects, I have poured so much of myself in them. But the funding is what it is and I have to be savvy. My biggest conundrum is whether savvy means relying on a strong track record or on a really snazzy idea. I can write a new boring R01 on project 1 on things I am proven to know how to do, or I can continue to pursue the very exciting project 2 where study sections are permanently worried about my expertise. I can't decide...

If you have not seen or read Sophie's Choice, it's worth it. Meryl Streep is amazing in it and she won an Oscar. Sophie is a Polish woman captured by the Nazis with her two children. As she enters Auschwitz she has to decide which one of her children will die. Which one will be more likely to survive the camp? Which one is the weakest needing more protection? Which one is the favorite? I have written many times of how my lab is split between two major projects, of how they are different in many ways, which is messing with my identity as a scientist. In addition, while they both were funded, one project has been struggling from the start and has required a huge amount of my attention and effort. The right people to carry it on have not materialized, so I have kept it going mostly by myself by sheer willpower and elbow grease. As I make the final tenure push, I have to decide whether to let it go. This feels like cutting out a piece of myself. This is the project that got me my job. It's the one that was my pride and joy as a postdoc, the one that made a beautiful job talk, and the one that was supposed to support my independent lab for years to come. It was not supposed to falter. It taught me that no matter how many brilliant ideas you have, your environment and your hires are critical for success. It required infrastructure that did not exist where I am and that had to be built from scratch without the proper support. It required equipment that was not available. Some major senior faculty stakeholders left to pursue other opportunities, collaborators who signed up to help did not deliver on their parts of the work. Funding runs out in a few months. The reviewers of the R01 application based on this work thought the hypothesis was interesting, but they wanted me to prove it. Which I cannot do without more money. So there. All in all, over four years we are talking of an investment of around $800K and I have to decide how much more time and money I really want to devote to it. The seed fell on ground that was not fertile enough for it to grow quickly.

The other child had been the recalcitrant one. Uncooperative and slow to develop, but it brought in money, so I kept it. I added it almost as an afterthought in my job talk, because I had a freaking K99 on it, so it would have looked weird if I ignored it. Opposite to the first one, this project required all my attention during my postdoc without much reward. Now the duckling has morphed into the most beautiful swan and we have three major papers in the pipeline. Because of the multiple personnel losses last summer, it stalled for six months and is now picking up again with new talented postdocs. My mentors tell me to cut my losses and go all in with this second project. Focus on getting the papers out to make this become my sure bet for an R01. Yet, I have come to my faculty position with an identity and a hypothesis I have been pursuing for 10 years, and I am faced with forsaking it. My gut is confused. I do not have the luxury of time to figure things out. In less than one year I have to start assembling my tenure package and I need an R01 to survive. I love both my projects, I have poured so much of myself in them. But the funding is what it is and I have to be savvy. My biggest conundrum is whether savvy means relying on a strong track record or on a really snazzy idea. I can write a new boring R01 on project 1 on things I am proven to know how to do, or I can continue to pursue the very exciting project 2 where study sections are permanently worried about my expertise. I can't decide...

Sunday, May 21, 2017

Is the pre-tenure job search a thing?

I recently posted a pool on twitter about when to apply for a new faculty position when you already have one.

I had often seen friends and colleagues apply when their tenure package went in to boost their leverage with current university and to see what was out there. I thought this is just what people do. My friend, who's a senior faculty member in engineering thought this was a terrible idea and that his department would immediately assume the candidate had been told they would not get tenure.

The poll which is not scientific, but had a good number of respondents, also suggested that a good time to look could be earlier than tenure, Year 3-4. But why would you leave that early when you have barely set up your lab?

I still don't know what is the "right" time and the reasons for doing a job search are many pre- or post-tenure.

The most obvious reason is that you really want to leave. Let's admit it. A lot of junior faculty candidates may not have many options or may not be savvy enough to ask all the right questions during their first search, so they end up in a situation which is not ideal. In addition, circumstances change: department chairs retire or move to a different position, colleagues move, deans and university presidents change and shift priorities, your significant other is in a different city. Or simply your research program brings you in a new direction and you need different equipment or resources.

But there is also the need for leverage. My assumption that the pre-tenure search was a frequent occurrence came from seeing multiple people do it, and not only get tenure, but also nice retention packages, because another school was trying to take them away. I have also seen senior academics play this game over and over again. The more competitive the university is, the more you need an outside offer to grab attention. A friend once complained "I feel the people who get the most are the ones constantly threatening to leave". So, you don't really want to leave, but you need something and you get it through a job search. This is a tricky proposition as senior administrators may not appreciate this game and it must be played very very shrewdly, especially if there is an expectation of loyalty. It may be more effective in larger places and it's not that you can ask "So, is the pre-tenure search a thing here?"

Yet, I personally think that if you are at all worried about tenure, it may not be a bad idea. The thing with tenure is that you don't necessarily know how it's going to go, unless you really trust your department and your university. I had friends who were told everything was great, but then were nixed by the department. Others had full departmental support and were nixed by a new senior administrator who suddenly changed the standards. Some of them really regret not doing a search after they obtained their first or second R01. Applying for jobs as a hot fully funded researcher has a very different vibe than applying after tenure denial. And going up for tenure with a few job offers makes sure you will land on your feet, no matter what.