When I started the blog 5 years ago (😱) some of my very first posts were about motivation, and I still need to remind myself of that advice from time to time. In one of my first posts I posted about a great book, Drive, by Daniel Pink who discusses behavioral research suggesting that once certain basic salary requirements are met people are motivated by Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose. They need to work independently and develop their own ideas. They need to feel that they have mastered complex theories and techniques. They need to have a good reason for why they are doing what they are doing.

This all sounds great! This is exactly what motivates me. But everyone moving at their own speed or following their own ideas could work for a large well-funded lab but may not be the best way to get a small research lab to finish the papers and projects we need to survive the tenure-track. I have already assigned lab peeps to specific priorities, but some of my mentors want me to pull people off their own projects to help on finishing other people's things. I'm debating whether that would help or hurt our progress. Will I be disrupting lab dynamics and upsetting egos? And what about their own projects? This doesn't really promote autonomy or mastery...

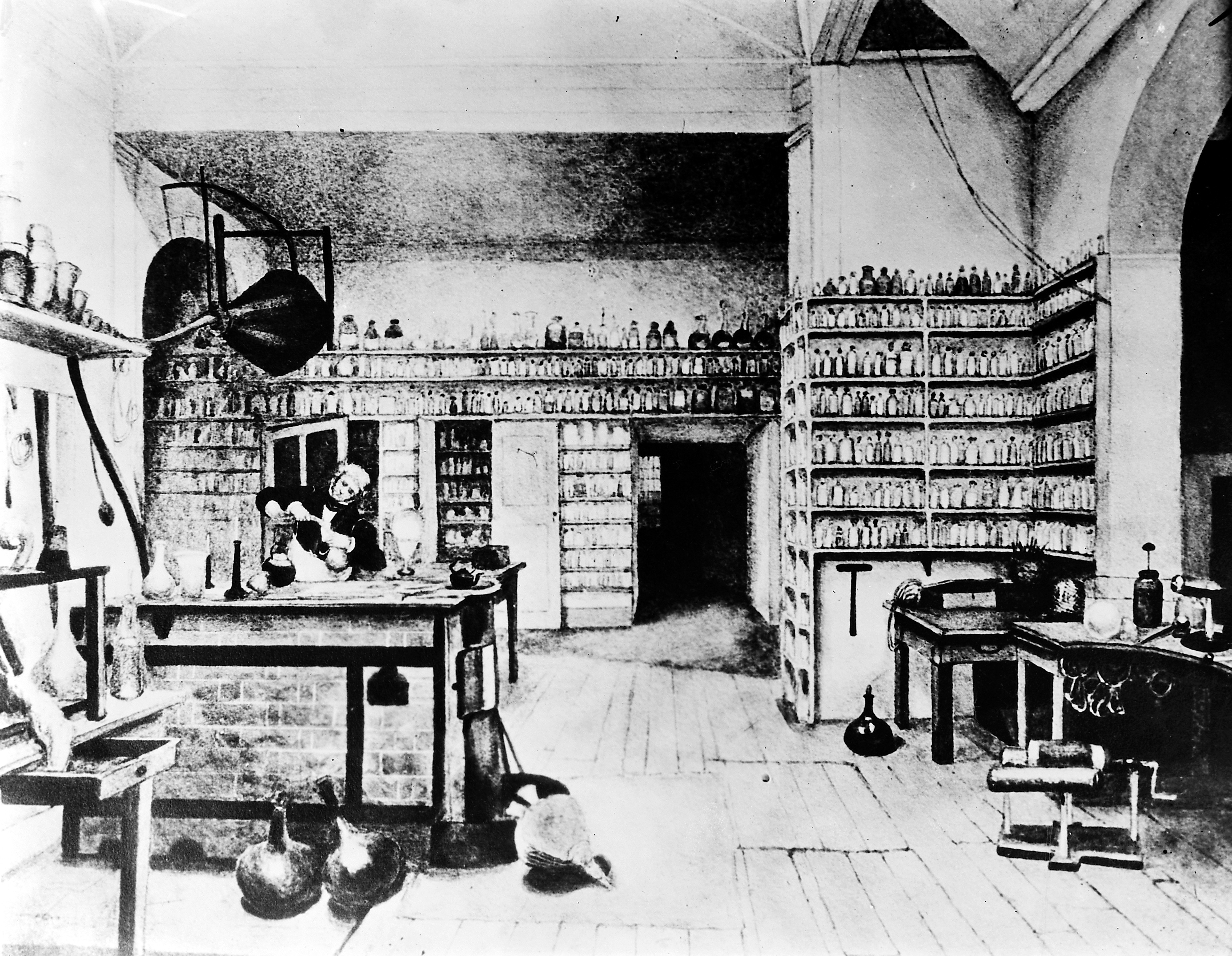

.jpg) It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?

It makes me think of the people who run a "tight ship". One of my past mentors forbade students to leave before 6pm and did random checks on Saturday to make sure everyone was at work. A lot got done, but I hated working that way, and this attitude is so distant from my personality, I would feel horrible imposing similar rules. But what is right? As I drive myself insane about the tenure push, I am torn about protecting my lab at all costs from my internal emotional turmoil... and again I am debating whether this is the best strategy. Will a false sense of security prevent my lab peeps from understanding that it's make or break time? That doom could be impending that we are all in this rowboat together. Everyone was warned very clearly of what joining a new investigator's laboratory entailed, of my timeline, and the pros and cons of coming in as tenure approached. But I feel that they really have no idea...and how could they?I think I need to better express my sense of urgency, keep stricter deadlines, and shift priorities if necessary...and of course get back in the lab! Maybe the camaraderie of working through this together is that is really needed. In the meantime, this handy productivity guide from the Harvard Business Review may also help!

Photo credit: By PeterJBellis from England (White Water Rafting (on The Nile) - Wikimedia Commons